Why is the Shoulder Girdle the Most Difficult Thing to Draw on the Human Body (part four)

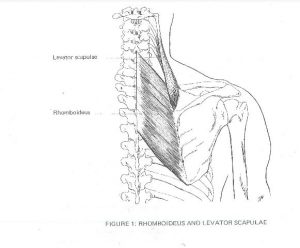

The last blog post delt with the back side of the shoulder girdle. We drew in the „rhomboideus“ and the „serratus“ and we explained their roles in the movement of the scapula forwards and backwards across the rib cage. The second direction of scapular movement is upwards and downwards. The muscles responsible for the movement upwards and downwards across the same old rib cage are called „levator anguli scapulae“ and „trapezius“.

The main reason the shoulder girdle is notoriously difficult to draw lies in the fact that the muscles lie on top of one another in layers and it’s difficult to tell them apart on the model. This is the case with „levator anguli scapulae“ (its name means the lifter of the angle of the scapula) and the trapezius- the leavtor is covered by the trapezius because it lies in the deeper muscular layer.

To quote the fabulous Richer’s anatomy: „levator anguli scapulae, origin: comes off the first transverse dorsal spine and „insertion:into the upper angle of the scapula“. The function of the muscle as described by Richer:“lifts the scapula towards the ears“. The levator also „melts“ with the muscles on the back of the neck called “the strong chords“ by painters and draftsmen.( I have extensively written about „the strong chords“ in the post about the neck.) The treatment of the the levator muscle and „the strong chords“ goes according to the old painterly rule which says that if the muscles perform the same function we treat them as a single mass. In case of the levator muscle, it means that we shall not treat it as a separate mass, apart from the other muscles holding the head vertically.

And this is the way Richer presents it:

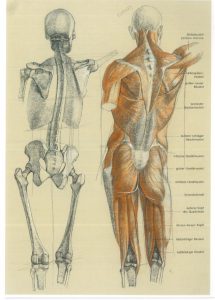

Lying across the layer, in which the „levator anguli scapulae“ and „rhomboideus“ are embedded, is „trapezius“. „Trapezius“ is a large muscle in three parts which covers a large surface area of rthe human back. According to Richer’s anatomy, its „origin“ is the „back of the skull“ and „the transverse processes of the 7th-2th dorsla spine“. That much is clear. The complicated part begins with Richer claiming that the „insertion“ of the muscle consists of three parts and all the three of them have a separate function. The first part consists of the upper fibres of the trapesius which insert into the end of the clavicle and into the acromion process. The function of those fibres is the lifting of the scapula. The middle part of the trapezius inserts into the spine of the scapula and thus completly covers it. Its function is to pull the scapula horisontally towards the spine. The third or the lowest part of the muscle ends on the inside of the spine of the scapula and pulls the scapula downwards and outwards.

And there is more to the trapezius… the painters love the details it has because it helps them render the drawing of the shoulder girdle more lifelike. There is an aponeurosis arond the transverse processes of the spine which make the vetebrae ( especially the seventh cervical) stand out more. The fibres of the trapezius end into the aponeurosis and thus do not bulge obscuring the processes. The outer edge of the trapezius is very interesting for artists because it moves across the muscles of the deeper layer of the back and thus clarifies its position in relation to the observer. The outer line of the trapezius thus moves over the „spina scapulae“, across the „scapulae“ themselves, over the „rhomboideus“ all the way to the 12th dorsal spine or the bottom of the rib cage ( where the tail of the trapezius ends).

Trapezius also has two indentations which came upon up beacuse of the way the muscle fibres insert into the aponeurosis of the spine of the scapula. They are very useful to artists because they help them locate the spine of the scapula and thus the scapula itself. This is how trapezius would look like with all of the details mentioned above:

This is the drawing of the trapesius from the celebrated anatomy of Gottfried Bammes „Die Gestalt des Menschen“ : Bammes in This ends the dorsal side of the shoulder girdle and in the next post we shall tackle its front. To reward our persistance in the pursuing of the truth of the shoulder girdle -a short poem by T.S. Eliott about the creative process and the troubles it ensues:

“So here I am, in the middle way, having had twenty years-

Twenty years largely wasted, the years of l’entre deux guerres-

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholy new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate,

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate – but there is no competition –

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.”

The featured drawing was taken from Hale’s “Anatomy Lessons from the Great Masters” and is a study by Michelanegelo. You should definetly aquire a copy of the book by Mr. Hale and ,if you have cash to spare, a drawing by Michelangelo. It will help you with your studies.

Najnoviji komentari