Why is the Shoulder Girdle the Most Difficult Thing to Draw on the Human Body (part seven)

If you had wished that the last post about the pectoralis muscle was the last one to deal with the subject, you are in for a disappontment for we shall continue to observe the pectorails in all its glory. Pectoralis plays an important role in construction of the torso and in this post we shall try to see how it looks like in the postiton “three quarters”.

Before attempting to draw the torso we shall have to come to a decision about its form, The torso consists primarily of the rib cage. The form for the rib cage we have been using up to now has been an ovoid. But ovoids are notoriously difficult to pinpoint in space: they do not show their postion in relation to the observer clearly. This is the reason the painters always try to locate the sternum before drawing the torso. The location of the sternum shows them how much the rib cage has rotated. R.B.Hale always emphasized that the painters are responsible for creating a everything in a painting: from a tilt the object has in in space to the light that falls upon the object. He continuosly claimed that painting is a process of designing not copying. Copying of what you see in front of you without reflection has never produced good results.

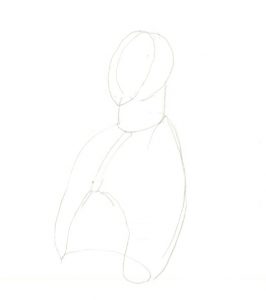

Let’s draw an ovoid rib cage with the breast bone positoned in “three quarters”. We can place the head and the neck on top of it.

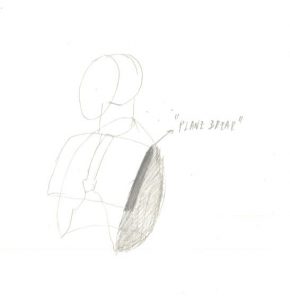

There is an important line on the ribcage called “the line of th angle of the ribs”. This line (has been discussed in great details) marks the exact location on the rib cage where the ribs change direction. The change of the direction of a form in space is very important, because this is the place where the the tonal change occurs on the object. Painters pay attention to that sort of stuff and they happen to love “the line of the angle of the ribs” because it’s an anatomical( really exsists on the body) plane break and they don’t need to imagine one. ( A plane break is the darkest spot on the plane that has changed direction. Knowledge of blane breaks is very important, because it’s a powerful means that helps achieve the illusion of threedimensionality. It’s importance is such that peinters save their contrasts for the “meeting of major light planes”)

Because the painterly need for plane breaks as a means of achieving a 3D effect is huge, the painters invent and imagine plane breaks in places where they aren’t entirely visible or even non-existant. This is the reason the pectoralis muscle is treated as a “curved paving block” according to R.B. Hale. In practice, that means that the painters tend to square up the pectoralis, because it gives the pectoralis a clear front and side plane which enables a clear tonal division. The effect the painters strive for is that of a light front plane with a darker side one.

If the lightning conditions remain the same as in the drawing above, the rib cage will repeat the same scheme of light and dark planes. The side plane remains in the dark, while the front plane is lit.

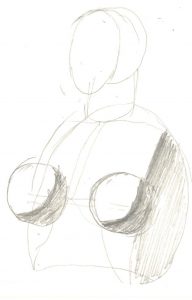

And if the aforementioned painters decided to draw a female torso instead of the male one – they would only need to add breasts to the already drawn rib cage. In the academic proportional system the breasts are supposed to be in the middle of the rib cage. The diameter of the academic breast equals 1/3 of the lenght of the rib cage. If the rib cage remains lit the same way as above, the sphere of the breast would be divided into two planes ( the same as the pectoral muscle and the rib cage).

The drawing below was made by Michelangelo. It can be found in the book called “Anatomy Lessons from the Great Masters” by R.B. Hale which was published by Watson and Guptil. In the drawing the pectoralis major takes up the entire space between the pit of the neck and the xiphoid process. Michelangelo emphasized the form of the xiphoid process which enables us to clearly determine the end and the begininng of the breast bone which is a very powerful tool for communicating the tilt of the torso. It also helps to make the rib cage more dynamic and more appealing to the eye.

Here’s what Hale had to say about the drawing:

” The massive blocklike pectoralis muscle in this well-developed male figure widens the chest beyond the area of the rib cage, but it still reveals the arched form of the rib cage beneath by the contours of its muscular bundles and grooves.”

The “paving block” Hale wrote about is the same one we’ve drawn on our simplified rib cages. ( without the tits, clearly)

Michelangelo’s drawing is full of wonderful anatomical details such as ribs visible through the flesh of the pectoralis. There are also muscular fibres visible close to the sternum where the muscle inserts. These are important details which add life to the nude drawing and make it more interesting. Michelangelo could pull it off because he didn’t really need a model to make a great nude drawing. I hope nobody thinks that the model looked exactly like the drawing and stood bent for hours. Michelangelo’s knowledge of anatomy was such that he could draw the model in any position and with any lightning he wished out of his head. That’s what being a master of anatomy means.

We need to try our best.

Najnoviji komentari