Why is the Shoulder Girdle the Most Difficult Thing to Draw on the Human Body (part six)

In the last post we’ve managed to succesfully finish the front part of the shoulder girdle with its famous pectoralis group. R.B. Hale, in his lectures about the pectoralis muscle, talks about birds and their strong pectoral muscles.

Flying birds have well developed pectoral muscles, beacause it’s precisely the pectoralis muscle which makes them fly. We have all seen chicken or turkey breast wrapped up in transparent plastic in the supemarket fridge. Those packed breasts are nothing else but giant pectoralis muscles even if turkeys and chickens are not especially good at flying. Their huge pectoralises, highly recommended for human consumption as a healthy and fat -free protein source, are artificially enlarged by cross breeding birds with huge pectoral muscles. Those poor pectoralises are artificially bred and have no real function on a living turkey. But we are not here to discuss the nutritional value of chicken pectoral muscles or the ethical background of breeding birds for human consumption. We are here to study the amazing science of anatomy and the enlarged pectoral muscle of a turkey is a wonderful and memorable example of a pectoral muscle in birds.

If we take into consideration that flying birds have large pectoral muscles, because they use them to lift themselves off the ground, we must logically assume that there must be an equally large bony structure that can support such a muscle. And it really is so.

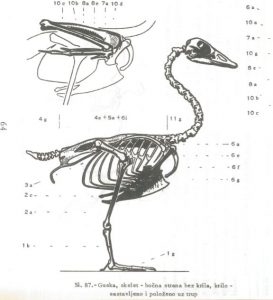

Let’s look at the drawing of a goose skeleton:

Let’s remind ourselves that the human pectoralis muscle starts at the sternum and has its insertion into the humerus. The equivalent of the human humerus in geese would be the bone postioned in its wings. But if we look closely at the goose skeleton in the drawing above, we will see that it was drawn without the wings. And that means that the long bone parallel to the goose’s backbone is actually the clavicle. The drawing of goose’s skeleton was taken from “Tieranatomie fuer Kuenstler” by W. Tank and here is what Herr Tank has to say about the peculiarties of the geese shoulder girdle ( in my own translation) :

“The shape of the shoulder girdle in birds is different than the one we are used to in quadrupeds. The scapula (6a) is a long, thin bone bent like a saber and it reaches almost to the pelvis. It’s parallel to the spine. Its front part forms a half of the glenoid cavity. The clavicles (6f) lie in front of the rib cage and are not connected to the sternum, they are actually grown together to form a “fork”. The “fork” of the clavicles is connected to the sternum in one place only and the connection isn’t a bony one. This makes the clavicles a stable support for the pectoral group.”

If you are gulity of watching silly american family comedies which take place on Christmas or Thanksgivinig or any such holyday which requires carnage of innocent poultry, there is a chance that you’ve whitnessed a custom of pulling on a turkey’s “wishbone” untill it breaks. Whoever ends up with a bigger piece of the “wishbone” has his wish granted. The “wishbone” is nothing but two bird’s clavicles grown together to accomodate the large pectoral muscle or (as Herr Tank has put it) the fork.

Pectoralis is the muscle which works against the force of gravity and lifts the fat bird of the ground. Therefore, it needs a strong and stable bony structure to enable it to do it. The human calvicle with its fragile sinewy joints which connects it to the sternum would break if we attemped to lift our fat asses off the ground.

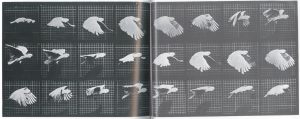

This is what a bird in flight looks like. A cockatoo, no less. Pay attention to the movement performed by the pectoralis.

The photgraphs of the cockatoo were taken from the “Complete Human and Animal Locomotion” by Eadweard Muybridge. I recommend the book fanatically.

To conclude: the pectoral muscle in birds covers almost whole of the clavicle and almost the entire humerus:

The above scheme was drawn by R.B. Hale in one of his famous lectures on pectoralis.

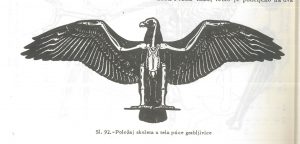

And this is what birds rib cage with wings would look like. Take a close look at the clavicles in front. They build the “fork” Herr Tank mentions and connect the wings to the rib cage.

If we look closely at the bones which are drawn “inside” the wings on the above drawing, we’ll soon notice that there are great similarities to the bones of the human arms. The bones are, actually, identical. The forarms consists of two bones, the arm only has one (the humerus) and the hand in birds has the tarsal and the metatarsal bones of a single finger. The whole structure is covered with feathers which have their own rules of growth.

When you are about to carve your next christmas goose or turkey- think about their bones and how they are identical to yours. And eat some tofu instead.

Najnoviji komentari